URBAN VISION

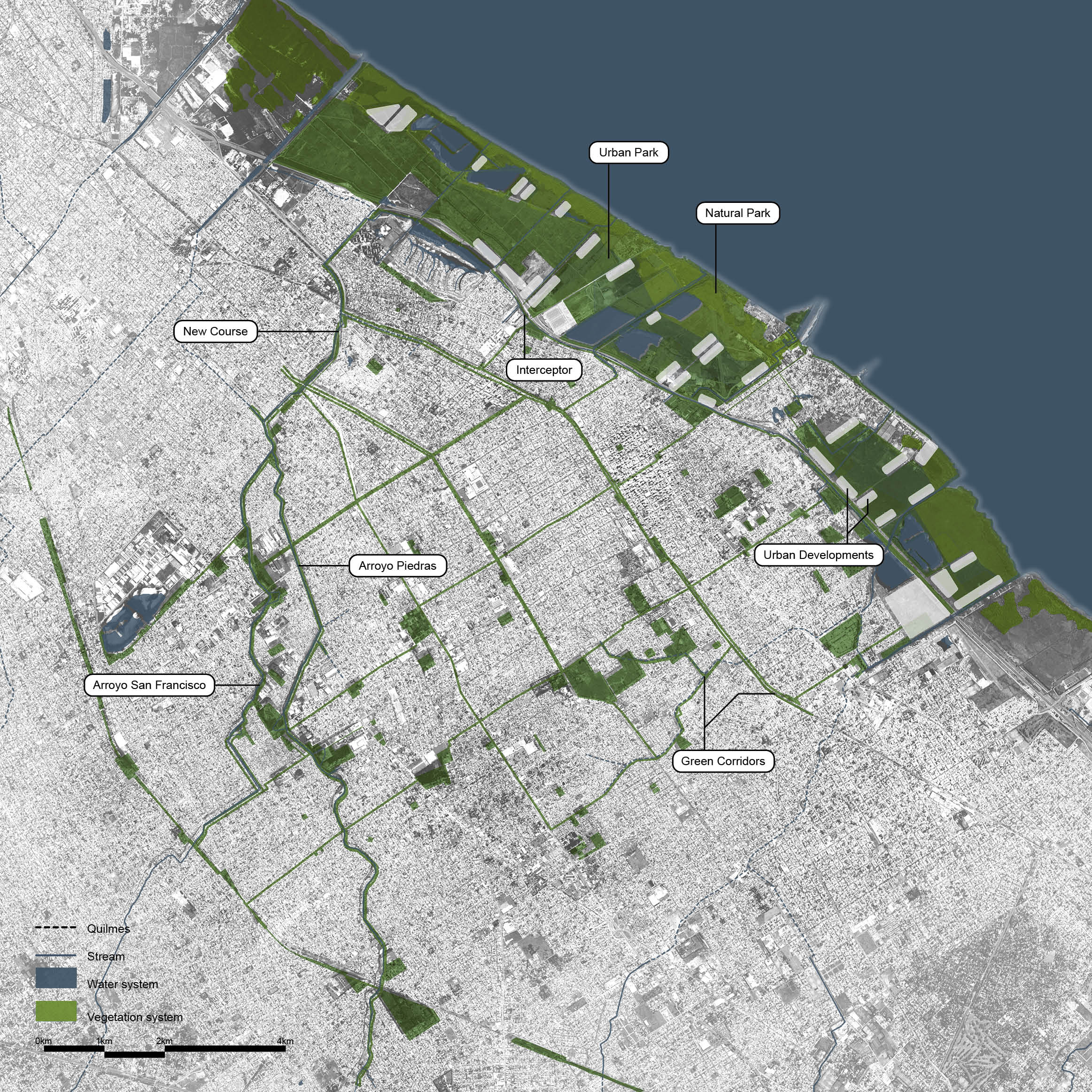

The improvement of water quality and the relation of citizenship with water courses serve as starting point to create a new system of public green spaces. The relation between the vegetation system and the hydrological system, the reorganization of the mobility system and consideration of a future careful development in the riverside composes a global vision for the city of Quilmes.

URBAN SYSTEMS

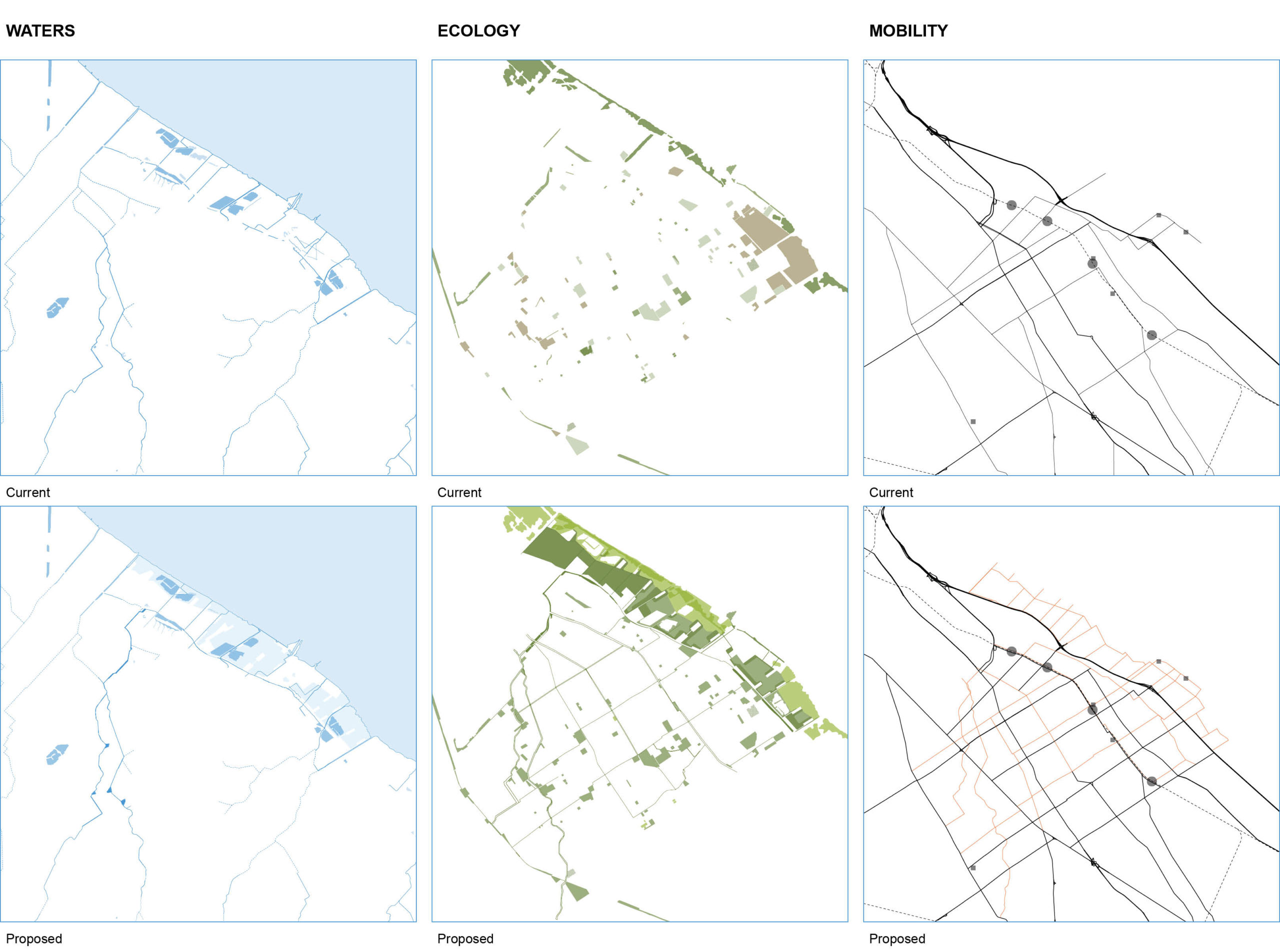

The city is understood through the overlapping of a number of different layers. In order to compose a global strategic vision for Quilmes and adress the various challenges of the city, three main urban systems are developed:

1. The hydrological system

2. The vegetation system

3. The mobility system

HUMAN DIMENSIONS

One key component of a healthy urban environment is the presence of publicly accessible blue and green spaces. Urban areas are made up of an interconnected system of buildings, gray spaces, green spaces, and blue spaces. Gray spaces are those open expanses between buildings containing hard infrastructure while green spaces consist of open areas with natural elements such as parks, playgrounds, and recreational fields1. Blue space summarizes all coastal and inland surface water features in the urban environment such as ponds, lakes, rivers, canals, and wetlands2. Traditionally considered a sub-category of green space, blue space is now seen as analogous to green space. Cities that are located by rivers or lakes, for example, often have a distinctive and unique physiognomy which creates their own special character3.

The city of Quilmes is located on the southern fluvial terrace of La Plata River. The city was originally cited on the high ground between the river and associated arroyos, natural gravity drainage creeks flowing into the river. Due to recent development of the low-lying La Plata riverside and surrounding marshes, sudestadas, or wind-driven ocean surges, often penetrate inland via overland flow and backflow through a series of highly channelized and disconnected arroyos or drainage creeks with little to no flood water retention capacity. Naturalizing the banks of the arroyos and edges of the La Plata River, development of riparian buffers along riverine corridors, and reestablishment of wetland systems for better stormwater collection and treatment should be a priority for Quilmes. Naturalization of waterways that have been channelized, straightened, or lined with concreate represents an opportunity to manage flooding in a more effective manner while enhancing the community’s connections to these waters. Because much of the flooding in Quilmes is caused by conditions that cross political jurisdictions, a more robust, watershed-based inventory and analysis of the interconnected network of blue and green spaces that impact the entire region is needed.

Such a network, properly developed, would not only reduce the risk of riverine and inland flooding in Quilmes, but would also enhance the health and wellbeing of its residents. A growing number of studies have posited a relationship between exposure to natural environments and community health and well-being outcomes. According to the World Health Organization, a healthy city offers physical and built environments that support health, recreation and wellbeing while providing accessible spaces for social interaction and enhancing community pride and cultural identity4. Availability of green spaces, for example, may provide opportunities for outdoor physical activities, social contacts, and relaxation and are often seen as determinants of the health of urban residents. Further, healthy coastal and riverine environments can have a positive effect on mental health and over and above the effects of green spaces5. Although not as broadly studied, the direct health benefits of blue and green spaces have also been recognized by researchers who acknowledge water features as important components of therapeutic landscapes. The concept of the therapeutic landscape is concerned with a holistic socio-ecological model of health that focuses on complex interactions that include the physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, societal, and environmental. Several studies have shown that contact with green spaces, for example, can be psychologically and physically restorative, reducing stress levels and adverse health outcomes.

Because the type and quality of urban blue and green spaces will influence resilience and human wellbeing in different ways depending on community characteristics, this research effort will utilize a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods to establish a broad range of socioeconomic and health indicators and assess how these interact with exposure to the natural environment by way of blue and green spaces. One aim to develop small area measures of ecosystem condition in order to assess blue and green space type and quality within the La Plata South Basin, including the city of Quilmes. Recent studies have found that the type, quality, and context of blue and green space should be considered in the assessment of the relationship between the natural environment, resilience, and human wellbeing. The quality and accessibility of blue and green spaces are key determinants of both the use of the space and the effectiveness of the spaces in enhancing the resilience and well-being of residents. People often choose to use or not use blue or green space not only for its features but also the condition of those ecosystem features and facilities. Spaces that are not maintained or that are in disrepair are less likely to be visited and contribute to a perceived lack of safety, which can act as an ecosystem disservice. Additionally, the types of natural spaces may promote physical activity to different extents. This project will utilize a coupled-human natural system framework that considers the components of the urban socioeconomic system, the urban ecosystem and ecosystem services. This framework will provide a means by which to gauge and monitor the effectiveness of blue and green spaces in creating healthy, safe, and resilient communities as well as to engage local communities in the decision-making process.

1 Magdalena van den Berg and others, ‘Health Benefits of Green Spaces in the Living Environment: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies’, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14.4 (2015), 806–16 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.008>.

2 Sebastian Völker and Thomas Kistemann, ‘The Impact of Blue Space on Human Health and Well-Being – Salutogenetic Health Effects of Inland Surface Waters: A Review’, International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 214.6 (2011), 449–60 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.05.001>; Benedict W Wheeler and others, ‘Beyond Greenspace: An Ecological Study of Population General Health and Indicators of Natural Environment Type and Quality’, International Journal of Health Geographics, 14.1 (2015) <https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-015-0009-5>.

3 Völker and Kistemann.

4 World Health Organization, Zagreb Declaration for Healthy Cities: Health and Health Equity in All Local Policies (Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2009).

5 Benedict W. Wheeler and others, ‘Does Living by the Coast Improve Health and Wellbeing?’, Health & Place, 18.5 (2012), 1198–1201 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.015>; Benedict W Wheeler and others.